The internet is abuzz with nostalgia for physical ebooks, a beloved yet abandoned medium. And it's easy to see why. As tangible objects storing encoded information, physical ebooks offered the flexibility of digital text combined with the permanence and offline accessibility of a hardcover book. They were collectible, lendable, private, and immune to later tampering or deletion. With so many compelling advantages, why did the industry cease production? More importantly, how can we bring them back?

In this brief oral history, we chronicle a fascinating detour into our reading past with the hope of shaping reading's future.

Mike: The Musician and Collector

Our first stop introduces Mike, an amateur music producer and consumer from Ontario, Canada. Mike primarily listens to MP3s purchased on Bandcamp, loaded onto his custom 3rd-Gen iPod. He also collects vinyl records when available and has even started collecting music on audio cassette, which he admits often "sounds objectively bad." When asked about physical ebooks, Mike expressed appreciation for their collectibility but found the secondhand market prices for these limited supply objects too high. "Just can't justify it to myself right now. Saw a guy on Marketplace selling a complete Dune set for $200. That was tempting."

Jon: The Incognito Digital Rights Advocate

Unlike Mike, Jon readily justifies the cost of collecting out-of-print physical ebooks. By day, Jon is a PhD candidate in neuroscience; by night, he scours the web for companies secretly spying on their customers. "Every one of these devices people have connects to the web for 'customer convenience,' he explains. "But half the software is there to spy on every click and report it back to daddy." Over the past decade, Jon has amassed a library of physical ebooks, which he reads on an old e-reader incapable of connecting to Wi-Fi. He paid for it in cash at a pawn shop. Asked why he doesn't simply buy paper books, which also don't spy on their readers, he gestures to a backpack in the corner. It's packed with essentials for when "the shit goes down," including a seed collection and a hard drive containing the entirety of Wikipedia.

Teresa: The Compassionate Caretaker

Teresa visited her great-grandmother Betty weekly during the last year of her life. As a young woman, Betty averaged 60 books per year, but as her eyesight and wrist strength waned, that number dwindled to almost zero. "It was heartbreaking to see," Teresa recalls. Amazon's Kindle had debuted the year prior, giving Teresa hope that its lightweight design and adjustable text size would revitalize Betty's favorite hobby. "She was adamant against signing up for Amazon because online shopping and 'buying digital' didn't make sense to her, and I didn't want to break her wishes by creating an account for her." But when physical ebooks entered the market the following year, they were a godsend. "She loved them. Slotting those cards in and out of the reader made intuitive sense, like a VHS tape, and she felt in control of the process."

Lizzie: The Frustrated Librarian

"My boss got super pissed," recounts Lizzie. Before leaving her workplace to homestead in 2013, Lizzie had spent eight years as a part-time assistant in a rural public library system, processing incoming books. "Our board wanted us to budget for either physical ebooks or online digital ebook leases, not both. It didn't make any sense not to do both. The board chair was really into Nooks and Kindles and thought physical ebooks were too backward." Just two years after the library committed to licensing online-delivered ebooks, their provider began raising rates and implementing caps on the number of times titles could be checked out. "She couldn't say anything publicly, but my boss went on huge rants behind closed doors about the missed opportunity to have our ebooks work like the rest of our physical collection," said Lizzie, referring to the first-sale doctrine.

Pete: The Pragmatic Pirate

During an Uber ride scheduled for our conversation with Pete, the rideshare driver told us he "refuses to blind-buy any book, movie, or CD on principle." Pete has been pirating since he bought his family their first home computer in 1997. "Now, if I like it, I will buy it. I'm not a 'thief,' even though that might be true in some technical sense. Just... I gotta know first if it's going to be worth handing over my income for." For a short period, Pete uploaded content for piracy. "Yeah, I bought some ebooks once and put the files online. Figured there are guys out there like me who might want to read some of these books before they plunk down ten, fifteen dollars for one." Asked if he ever pirated a physical ebook, he shared that he bought some Larry McMurtry novels in that format, but it was "too much of a pain in the ass" to transfer the file off the specialized cartridges. "With the digitals, you got the file on your computer already. Less fuss there."

Romantasy Ratatouille / Interlibrary Leanne: A Glimmer of Hope

In the almost two decades since the last physical ebook was produced, the very idea of this format has largely vanished from popular consciousness. But that's changing, with TikTokers and Redditors waxing nostalgic over the lost cartridges. Moreover, in niche areas, some version of the concept is gaining momentum for a comeback.

A Kickstarter page for leasing key supply chain sites to produce physical ebooks has had a strong start since its launch this summer. It's backed by popular book YouTubers like Ratatouille99 and BelleIRL, who often cover 'romantasy' series that regularly spawn double-digit spin-offs. These series often arrive without major publisher backing on platforms like Kindle Unlimited and never see print runs. More fervent parts of the community want to buy copies of the books to keep and display but want them to remain digital, which ‘feels’ truer to their origins. BelleIRL has said she wants to see her favorite series packaged into elaborate packaging with new commissioned artwork.

These initiatives have sparked curiosity from interlibrary loan units in academic libraries. One ILL staffer we spoke to, Leanne, said the libraries in her state have considered the possibility of key cards for sharing digital-only scholarly books and academic journal articles. "We had a one-two punch this year," Leanne described, "between CDL (controlled digital lending) seeming to become more restrictive after Hachette (Hachette Book Group, Inc. v. Internet Archive) on the one hand, and seeing ILL on the chopping block with the proposed IMLS cuts."

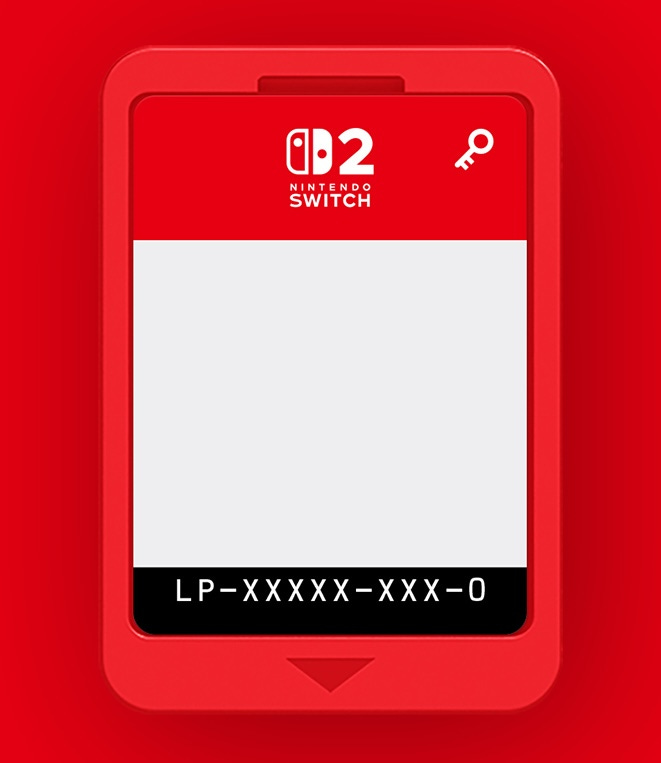

The 'key cards' concept is based on new Nintendo Switch 2 game cards, which don't actually contain the game file but rather permissions to access game data from the cloud. Mailing key cards through regular post would save on costs while potentially appeasing publishers who have sued over projects they've claimed are overly permissive, like the National Emergency Library.

While key cards for academic materials are different from physical ebooks, which contain actual content files, both proposed cartridges could rely on similar manufacturing processes making the prospect more viable for makers. The two ideas also share a common vision for bringing a tangible element back to a largely digital arena, which since its inception has been largely governed by an extralegal copyright regime imposed by publishers. "The overreach has been crazy," Leanne said. "It didn't used to be like this when all books were just, like, real objects."